|

| 1 | +# Inside the V8 Engine and How to write optimized code |

| 2 | + |

| 3 | +## What is a JS engine? |

| 4 | + |

| 5 | +A JavaScript engine is a program or an interpreter which executes JavaScript code. |

| 6 | + |

| 7 | +In particular, A JavaScript engine can be implemented as a just-in-time compiler compiles JavaScript to bytecode in some form. |

| 8 | + |

| 9 | +V8 is the most popular among JS engines, however, there are other projects that are implementing a JavaScript engine: |

| 10 | + |

| 11 | +- V8 - an open source developed by Google, written in C++ |

| 12 | + |

| 13 | +- Rhino - an open source managed by Mozilla Foundation, written in Java |

| 14 | + |

| 15 | +- SpiderMonkey - the first JavaScript engine |

| 16 | + |

| 17 | +- JavaScriptCore - an open source, developed by Apple for Safari |

| 18 | + |

| 19 | +- Chakra (JScript9) - a JavaScript engine for Internet Explorer |

| 20 | + |

| 21 | +- JerryScript - a lightweight engine for IoT |

| 22 | + |

| 23 | +Now, we will back to the V8 to explore more details. |

| 24 | + |

| 25 | +## Why was the V8 Engine created? |

| 26 | + |

| 27 | +The V8 Engine which is built by Google is open source and written in C++. This engine is used inside Google Chrome. Unlike the rest of the engines, however, V8 is also used for the popular Node.js runtime. |

| 28 | + |

| 29 | +V8 was first designed to increase the performance of JavaScript inside web browsers. To do that, V8 translates JS code into more efficient machine code instead of using an interpreter by implementing a JIT (just-in-time) compiler. However, unlike modern JavaScript engines do such as SpiderMonkey or Rhino, V8 doesn't proceduce bytecode or any intermidiate code. |

| 30 | + |

| 31 | +## V8 used to have 2 compilers |

| 32 | + |

| 33 | +- full-codegen: a simple and very fast compiler that produced simple and relatively slow machine code. |

| 34 | + |

| 35 | +- Crankshaft: a more complex (JIT) optimizing compiler that procduced highly-optimized code. |

| 36 | + |

| 37 | +Moreover, V8 engine also uses several threads internally: |

| 38 | + |

| 39 | +- The main thread does what you expect: fetch the code, compile the code and then execute it. |

| 40 | + |

| 41 | +- There is also a separate thread for compiling, so that the main thread can keep executing while the former is optimizing the code. |

| 42 | + |

| 43 | +- A Profiler thread that will tell the runtime on which methods we spend a lot of time so that Crankshaft can optimize them. |

| 44 | + |

| 45 | +- A few threads to handle Garbage Collector sweeps. |

| 46 | + |

| 47 | +When first execute the JS code, V8 leverages full-codegen which directly translates the parsed JavaScript into machine code without any transformation. This allows it to start executing machine code very fast. Note that V8 does not use intermediate bytecode representation this way removing the need for an interpreter. |

| 48 | + |

| 49 | +When your code has run for some time, the profiler thread has gathered enough data to tell which method should be optimized. |

| 50 | + |

| 51 | +Next, Crankshaft optimizations begin in another thread. It translates the JavaScript abstract syntax tree to a high-level static single-assignment (SSA) representation called `Hydrogen` and tries to optimize that `Hydrogen` graph. Most optimizations are done at this level. |

| 52 | + |

| 53 | +So, what optimization Crankshaft does with our JavaScript code? |

| 54 | + |

| 55 | +## Inlining |

| 56 | + |

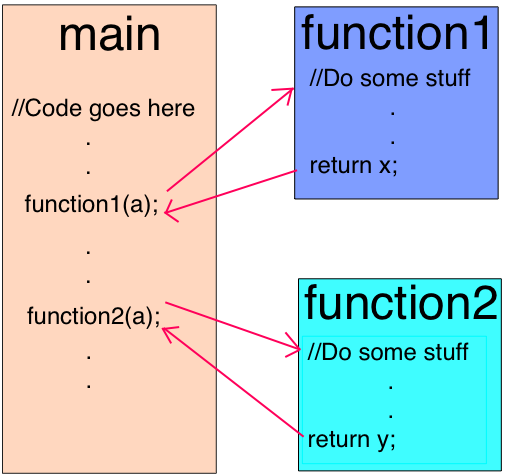

| 57 | +The first optimization is inlining as much code as possible in advance. Inlining is the process of replacing a call site (the line of code where the function is called) with the body of the called function. This simple step allows following optimizations to be more meaningful. |

| 58 | + |

| 59 | + |

| 60 | + |

| 61 | +## Hidden classes |

| 62 | + |

| 63 | +Javascript is a prototype-based programming language, thought it now has `class` declaration in ES6. |

| 64 | +There are no classes and objects are created using a cloning process. |

| 65 | + |

| 66 | +Hidden classes work similarly to the fixed object layouts (classes) used in languages like Java, except they are created at runtime. Now, let’s see what they actually look like: |

| 67 | + |

| 68 | +```javascript |

| 69 | +function Point(x, y) { |

| 70 | + this.x = x; |

| 71 | + this.y = y; |

| 72 | +} |

| 73 | + |

| 74 | +var point1 = new Point(1, 2); |

| 75 | +console.log(point1); |

| 76 | +``` |

| 77 | + |

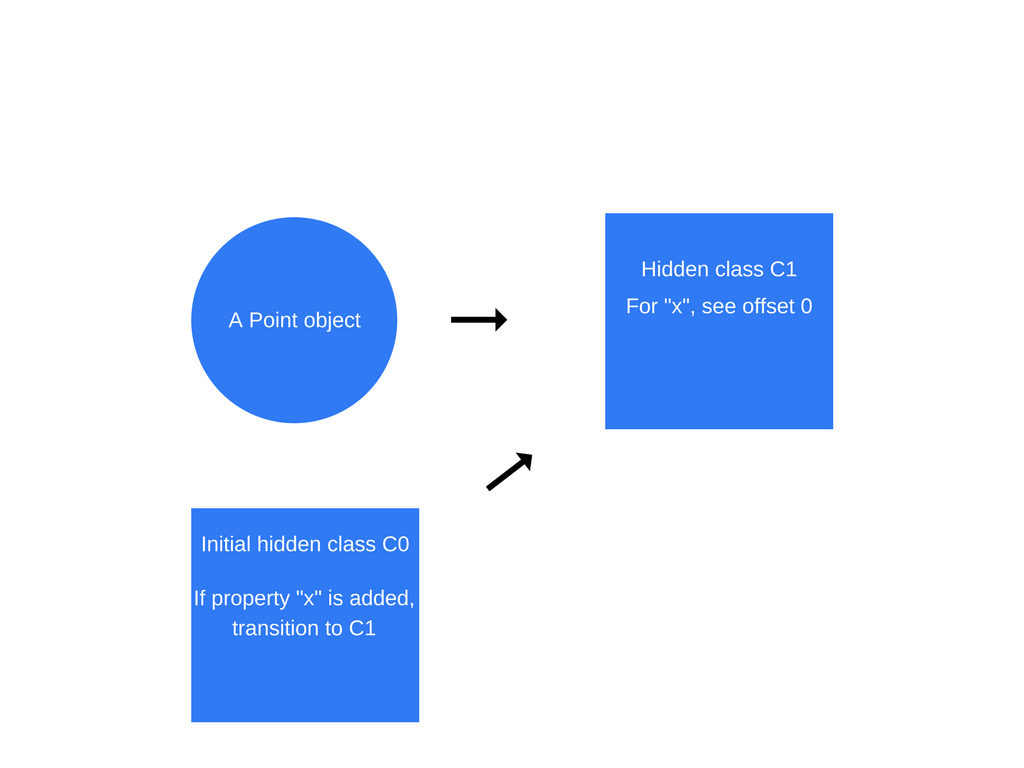

| 78 | +Once the “new Point(1, 2)” invocation happens, V8 will create a hidden class called “C0”. |

| 79 | + |

| 80 | + |

| 81 | + |

| 82 | +No properties have been defined for Point yet, so “C0” is empty. |

| 83 | + |

| 84 | +Once the first statement “this.x = x” is executed (inside the “Point” function), V8 will create a second hidden class called “C1” that is based on “C0”. “C1” describes the location in the memory (relative to the object pointer) where the property x can be found. In this case, “x” is stored at offset 0, which means that when viewing a point object in the memory as a continuous buffer, the first offset will correspond to property “x”. V8 will also update “C0” with a “class transition” which states that if a property “x” is added to a point object, the hidden class should switch from “C0” to “C1”. The hidden class for the point object below is now “C1”. |

| 85 | + |

| 86 | + |

| 87 | + |

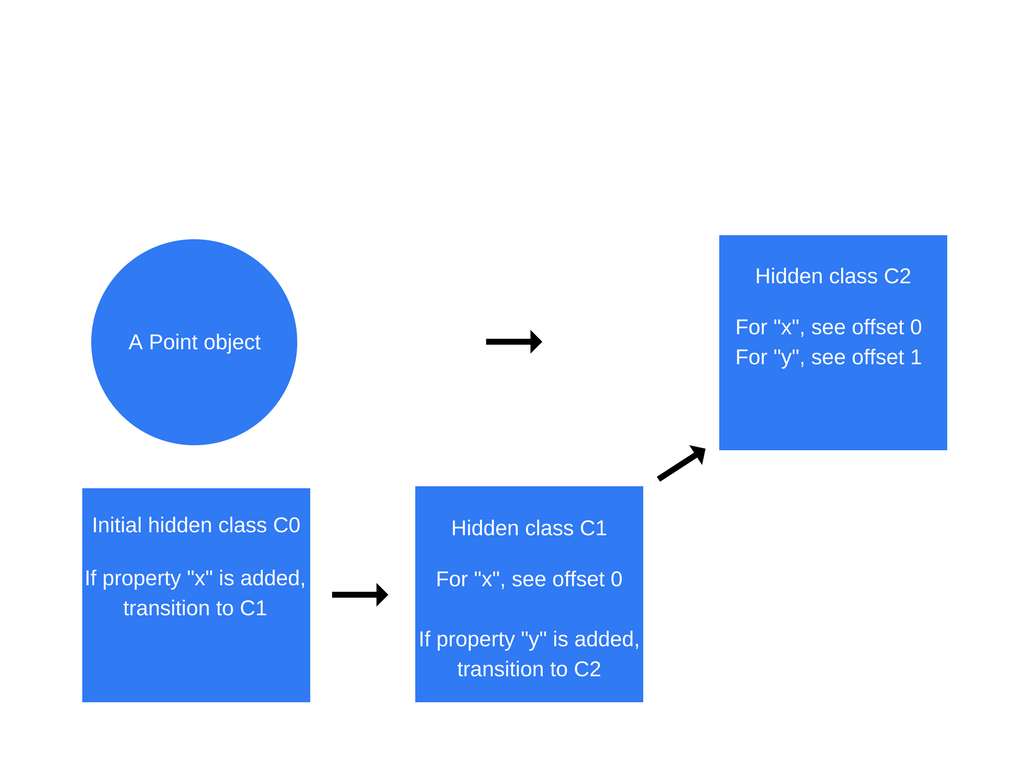

| 88 | +A new hidden class called “C2” is created, a class transition is added to “C1” stating that if a property “y” is added to a Point object (that already contains property “x”) then the hidden class should change to “C2”, and the point object’s hidden class is updated to “C2”. |

| 89 | + |

| 90 | + |

| 91 | + |

| 92 | +Hidden class transitions are dependent on the order in which properties are added to an object. Take a look at the code snippet below: |

| 93 | + |

| 94 | +```javascript |

| 95 | +function Point(x, y) { |

| 96 | + this.x = x; |

| 97 | + this.y = y; |

| 98 | +} |

| 99 | +var p1 = new Point(1, 2); |

| 100 | +p1.a = 5; |

| 101 | +p1.b = 6; |

| 102 | +var p2 = new Point(3, 4); |

| 103 | +p2.b = 7; |

| 104 | +p2.a = 8; |

| 105 | +``` |

| 106 | + |

| 107 | +Now, you would assume that for both p1 and p2 the same hidden classes and transitions would be used. Well, not really. For “p1”, first the property “a” will be added and then the property “b”. For “p2”, however, first “b” is being assigned, followed by “a”. Thus, “p1” and “p2” end up with different hidden classes as a result of the different transition paths. In such cases, it’s much better to initialize dynamic properties in the same order so that the hidden classes can be reused. |

| 108 | + |

| 109 | +## Inline caching |

| 110 | + |

| 111 | +V8 takes advantage of another technique for optimizing dynamically typed languages called inline caching. Inline caching relies on the observation that repeated calls to the same method tend to occur on the same type of object. An in-depth explanation of inline caching can be found [here](https://github.com/sq/JSIL/wiki/Optimizing-dynamic-JavaScript-with-inline-caches). |

| 112 | + |

| 113 | +Let's consider an example: |

| 114 | + |

| 115 | +```javascript |

| 116 | +const divide = (lhs, rhs) => { |

| 117 | + return lhs / rhs; |

| 118 | +}; |

| 119 | + |

| 120 | +const divideSomeNumbers = (lhsArray, divisor, resultArray) => { |

| 121 | + for (let i = 0; i < lhsArray.length; i++) { |

| 122 | + resultArray[i] = divide(lhsArray[i], divisor); |

| 123 | + } |

| 124 | + |

| 125 | + return resultArray; |

| 126 | +}; |

| 127 | +``` |

| 128 | + |

| 129 | +This test case is pretty simple, there are many ways you can optimize it. Let's choose a toy optimization to demonstrate what kind of code an inline cache might generate in this scenario - using bitwise arithmetic to do division. |

| 130 | + |

| 131 | +When dividing an integer by a power of two, you can use a bitwise shift instead of a divide to get the same result. A bitwise shift is considerably simpler to implement, so in cases where the divisor (the right hand side) is known to be a power of two, a compiler might turn a division into a bitwise shift. |

| 132 | + |

| 133 | +```javascript |

| 134 | +var dividers = { |

| 135 | + 2: function divideBy2(lhs, unused) { |

| 136 | + return lhs >> 1; |

| 137 | + }, |

| 138 | + 4: function divideBy4(lhs, unused) { |

| 139 | + return lhs >> 2; |

| 140 | + }, |

| 141 | + undefined: function divideByNumber(lhs, rhs) { |

| 142 | + return lhs / rhs; |

| 143 | + } |

| 144 | +}; |

| 145 | + |

| 146 | +function divideSomeNumbers(lhsArray, divisor, resultArray) { |

| 147 | + var divider = dividers[divisor]; |

| 148 | + for (let i = 0; i < lhsArray.length; i++) { |

| 149 | + resultArray[i] = divider(lhsArray[i], divider); |

| 150 | + } |

| 151 | +} |

| 152 | +``` |

| 153 | + |

| 154 | +Cool, that looks good. But wait! We replaced a call to a known method - divide - with a call to a method that is chosen at runtime. And that method depends on the arguments to our function! Did we just make it slower? Quite possibly - unless the JIT is smart enough, every call to divider will be a virtual call of some sort, and this might prevent inlining and other key optimizations. |

| 155 | + |

| 156 | +How does it work, actually? V8 maintains a cache of the type of objects that were passed as a parameter in recent method calls and uses this information to make an assumption about the type of object that will be passed as a parameter in the future. If V8 is able to make a good assumption about the type of object that will be passed to a method, it can bypass the process of figuring out how to access the object’s properties, and instead, use the stored information from previous lookups to the object’s hidden class. |

0 commit comments