Tutorial: Advection Equation with data driven DeepONet¶

+++⚠️ Before starting:¶

We assume you are already familiar with the concepts covered in the Getting started with PINA tutorials. If not, we strongly recommend reviewing them before exploring this advanced topic.

+

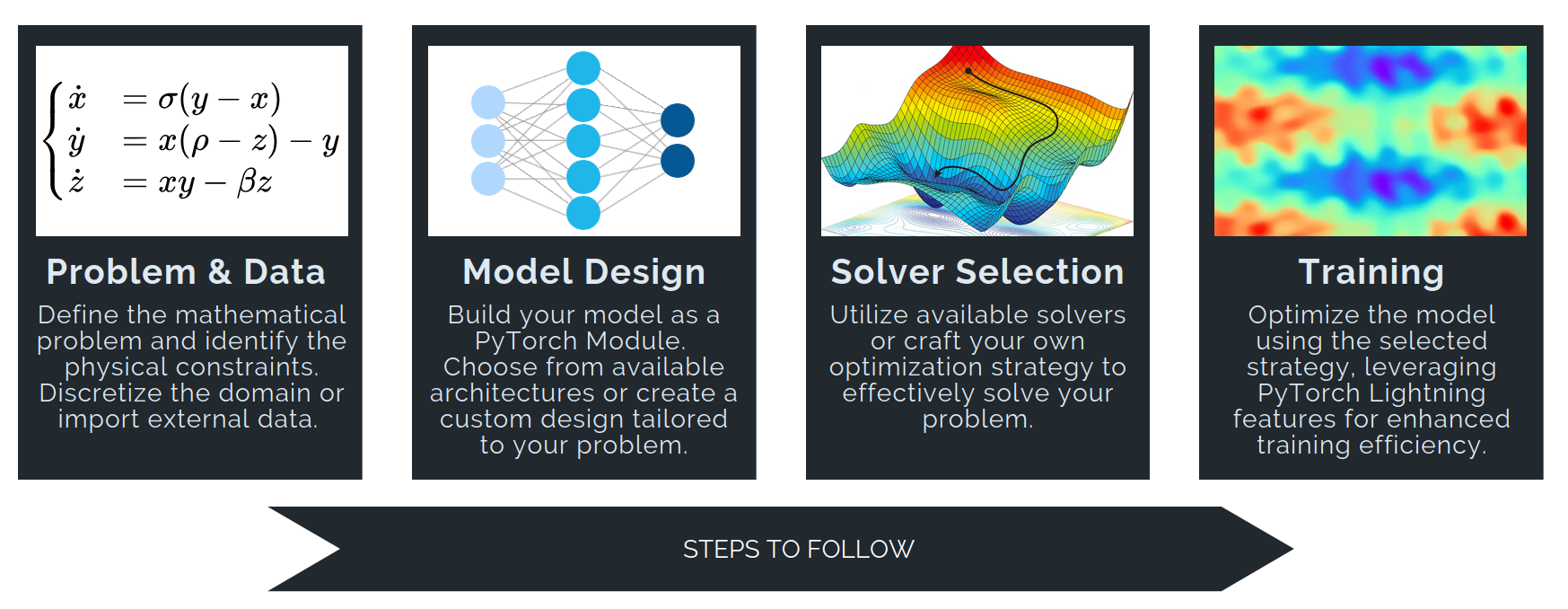

In this tutorial, we demonstrate how to solve the advection operator learning problem using DeepONet. We follow the original formulation of Lu et al. in DeepONet: Learning nonlinear operators for identifying differential equations based on the universal approximation theorem of operator.

We begin by importing the necessary modules.

+## routine needed to run the notebook on Google Colab

+try:

+ import google.colab

+

+ IN_COLAB = True

+except:

+ IN_COLAB = False

+if IN_COLAB:

+ !pip install "pina-mathlab[tutorial]"

+ # get the data

+ !mkdir "data"

+ !wget "https://github.com/mathLab/PINA/raw/refs/heads/master/tutorials/tutorial24/data/advection_input_testing.pt" -O "data/advection_input_testing.pt"

+ !wget "https://github.com/mathLab/PINA/raw/refs/heads/master/tutorials/tutorial24/data/advection_input_training.pt" -O "data/advection_input_training.pt"

+ !wget "https://github.com/mathLab/PINA/raw/refs/heads/master/tutorials/tutorial24/data/advection_output_testing.pt" -O "data/advection_output_testing.pt"

+ !wget "https://github.com/mathLab/PINA/raw/refs/heads/master/tutorials/tutorial24/data/advection_output_training.pt" -O "data/advection_output_training.pt"

+

+import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

+import torch

+import warnings

+from functools import partial

+

+

+from pina import Trainer, LabelTensor

+from pina.model import FeedForward, DeepONet

+from pina.solver import SupervisedSolver

+from pina.problem.zoo import SupervisedProblem

+from pina.loss import LpLoss

+

+warnings.filterwarnings("ignore")

+Advection problem and data preparation¶

We consider the 1D advection equation +$$ +\frac{\partial u}{\partial t} + \frac{\partial u}{\partial x} = 0, +\quad x \in [0,2], \; t \in [0,1], +$$ +with periodic boundary conditions. The initial condition is chosen as a Gaussian pulse centered at a random location +$\mu \sim U(0.05, 1)$ and with variance $\sigma^2 = 0.02$: +$$ +u_0(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\pi\sigma^2}} e^{-\frac{(x - \mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}}, +\quad x \in [0,2]. +$$

+Our goal is to learn the operator

+$$

+\mathcal{G}: u_0(x) \mapsto u(x, t = \delta) = u_0(x - \delta),

+$$

+with $\delta = 0.5$ for this tutorial. In practice, this means learning a mapping from the initial condition to the solution at a fixed later time.

+The dataset therefore consists of trajectories where inputs are initial profiles and outputs are the same profiles shifted by $\delta$.

The data has shape [T, Nx, D], where:

-

+

T— number of trajectories (100 for training, 1000 for testing),

+Nx— number of spatial grid points (fixed at 100),

+D = 1— single scalar field valueu.

+

We now load the dataset and visualize sample trajectories.

+# loading training data

+data_0_training = LabelTensor(

+ torch.load("data/advection_input_training.pt", weights_only=False),

+ labels="u0",

+)

+data_dt_training = LabelTensor(

+ torch.load("data/advection_output_training.pt", weights_only=False),

+ labels="u",

+)

+

+# loading testing data

+data_0_testing = LabelTensor(

+ torch.load("data/advection_input_testing.pt", weights_only=False),

+ labels="u0",

+)

+data_dt_testing = LabelTensor(

+ torch.load("data/advection_output_testing.pt", weights_only=False),

+ labels="u",

+)

+The data are loaded, let's visualize a few of the initial conditions!

+# storing the discretization in space:

+Nx = data_0_training.shape[1]

+

+for idx, i in enumerate(torch.randint(0, data_0_training.shape[0] - 1, (3,))):

+ u0 = data_0_training[int(i)].extract("u0")

+ u = data_dt_training[int(i)].extract("u")

+ x = torch.linspace(

+ 0, 2, Nx

+ ) # the discretization in the spatial dimension is fixed

+ plt.subplot(3, 1, idx + 1)

+ plt.plot(x, u0.flatten(), label=rf"$u_0(x)$")

+ plt.plot(x, u.flatten(), label=rf"$u(x, t=\delta)$")

+ plt.xlabel(rf"$x$")

+ plt.tight_layout()

+ plt.legend()

+Great — we have generated a traveling wave and visualized a few samples. Next, we will use this data to train a DeepONet.

DeepONet¶

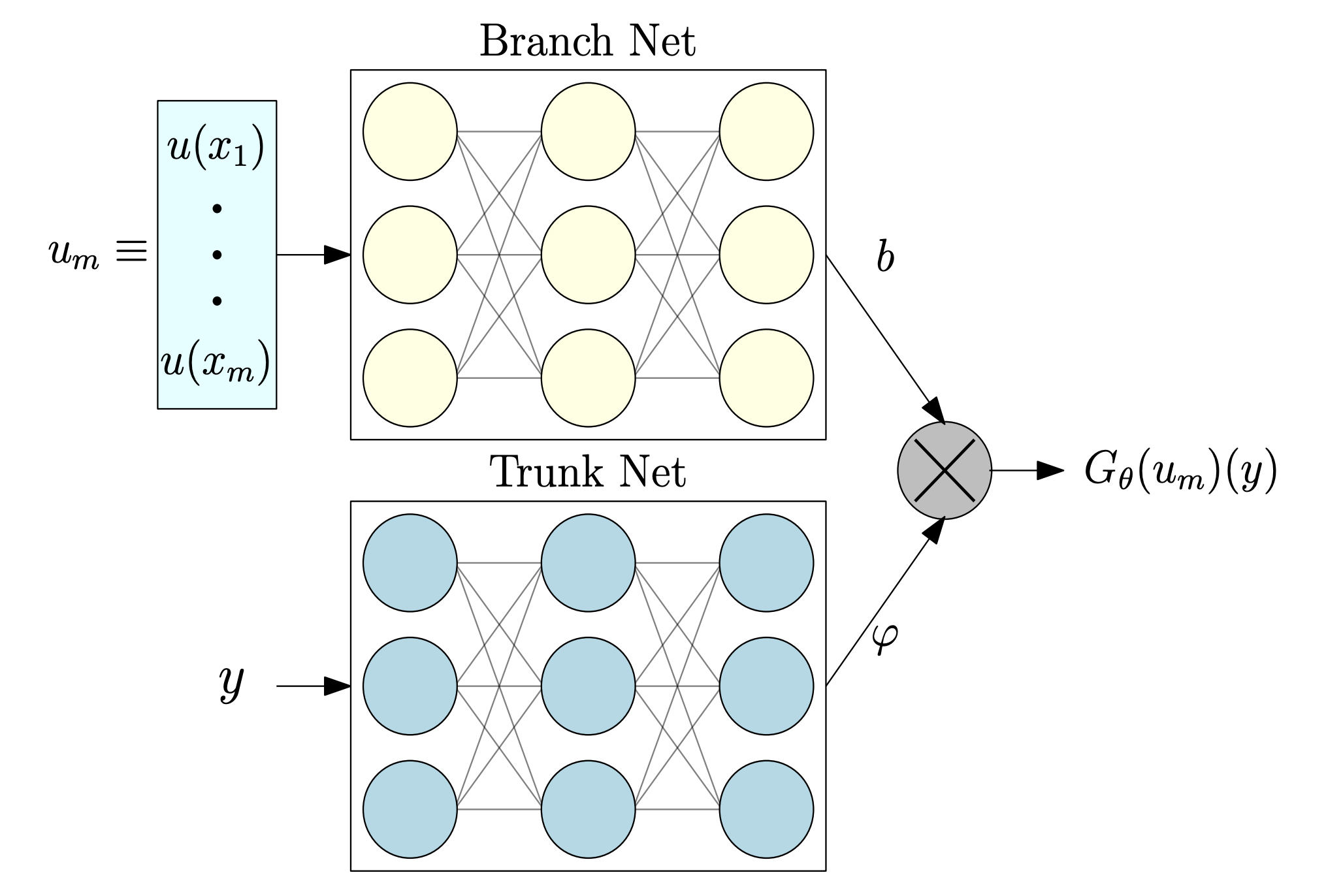

The standard DeepONet architecture consists of two subnetworks: a branch network and a trunk network (see figure below).

+

+In our setting:

+-

+

- The branch network receives the initial condition of each trajectory, with input shape

[B, Nx]— whereBis the batch size andNxthe spatial discretization points of the field at ( t = 0 ).

+ - The trunk network takes input of shape

[B, 1], corresponding to the location at which we evaluate the solution (in this 1D case, the spatial coordinate).

+

Together, these networks learn the mapping from the initial field to the solution at a later time.

+We now define and train the model for the advection problem.

+problem = SupervisedProblem(

+ input_=data_0_training,

+ output_=data_dt_training,

+ input_variables=data_0_training.labels,

+ output_variables=data_dt_training.labels,

+)

+We now proceede to create the trunk and branch networks.

+# create Trunk model

+class TrunkNet(torch.nn.Module):

+ def __init__(self, **kwargs):

+ super().__init__()

+ self.trunk = FeedForward(**kwargs)

+

+ def forward(self, x):

+ t = (

+ torch.zeros(size=(x.shape[0], 1), requires_grad=False) + 0.5

+ ) # create an input of only 0.5

+ return self.trunk(t)

+

+

+# create Branch model

+class BranchNet(torch.nn.Module):

+ def __init__(self, **kwargs):

+ super().__init__()

+ self.branch = FeedForward(**kwargs)

+

+ def forward(self, x):

+ return self.branch(x.flatten(1))

+The TrunkNet is implemented as a standard FeedForward network with a slightly modified forward method. In this case, the trunk network simply outputs a tensor filled with the value (0.5), repeated for each trajectory — corresponding to evaluating the solution at time (t = 0.5).

The BranchNet is also a FeedForward network, but its forward pass first flattens the input along the last dimension. This produces a vector of length Nx, representing the sampled initial condition at the sensor locations.

With both subnetworks defined, we can now instantiate the DeepONet model using the DeepONet class from pina.model.

# initialize truck and branch net

+trunk = TrunkNet(

+ layers=[256] * 4,

+ output_dimensions=Nx,

+ input_dimensions=1, # time variable dimension

+ func=torch.nn.ReLU,

+)

+branch = BranchNet(

+ layers=[256] * 4,

+ output_dimensions=Nx,

+ input_dimensions=Nx, # spatial variable dimension

+ func=torch.nn.ReLU,

+)

+

+# initialize the DeepONet model

+model = DeepONet(

+ branch_net=branch,

+ trunk_net=trunk,

+ input_indeces_branch_net=["u0"],

+ input_indeces_trunk_net=["u0"],

+ reduction="id",

+ aggregator="*",

+)

+The aggregation and reduction functions combine the outputs of the branch and trunk networks. In this example, their outputs are multiplied element-wise, and no reduction is applied — meaning the final output has the same dimensionality as each network’s output.

+We train the model using a SupervisedSolver with an MSE loss. Below, we first define the solver and then the trainer used to run the optimization.

# define solver

+solver = SupervisedSolver(problem=problem, model=model)

+

+# define the trainer and train

+trainer = Trainer(

+ solver=solver, max_epochs=200, enable_model_summary=False, accelerator="cpu"

+)

+trainer.train()

+💡 Tip: For seamless cloud uploads and versioning, try installing [litmodels](https://pypi.org/project/litmodels/) to enable LitModelCheckpoint, which syncs automatically with the Lightning model registry. ++

GPU available: False, used: False ++

TPU available: False, using: 0 TPU cores ++

`Trainer.fit` stopped: `max_epochs=200` reached. ++

Let's see the final train and test errors:

+# the l2 error

+l2 = LpLoss()

+

+with torch.no_grad():

+ train_err = l2(trainer.solver(data_0_training), data_dt_training)

+ test_err = l2(trainer.solver(data_0_testing), data_dt_testing)

+

+print(f"Training error: {float(train_err.mean()):.2%}")

+print(f"Testing error: {float(test_err.mean()):.2%}")

+Training error: 0.87% +Testing error: 1.58% ++

We can see that the testing error is slightly higher than the training one, maybe due to overfitting. We now plot some results trajectories.

+for i in [1, 2, 3]:

+ plt.subplot(3, 1, i)

+ plt.plot(

+ torch.linspace(0, 2, Nx),

+ solver(data_0_training)[10 * i].detach().flatten(),

+ label=r"$u_{NN}$",

+ )

+ plt.plot(

+ torch.linspace(0, 2, Nx),

+ data_dt_training[10 * i].extract("u").flatten(),

+ label=r"$u$",

+ )

+ plt.xlabel(r"$x$")

+ plt.legend(loc="upper right")

+ plt.show()

+As we can see, they are barely indistinguishable. To better understand the difference, we now plot the residuals, i.e. the difference of the exact solution and the predicted one.

+for i in [1, 2, 3]:

+ plt.subplot(3, 1, i)

+ plt.plot(

+ torch.linspace(0, 2, Nx),

+ data_dt_training[10 * i].extract("u").flatten()

+ - solver(data_0_training)[10 * i].detach().flatten(),

+ label=r"$u - u_{NN}$",

+ )

+ plt.xlabel(r"$x$")

+ plt.tight_layout()

+ plt.legend(loc="upper right")

+What's Next?¶

We have seen a simple example of using DeepONet to learn the advection operator. This only scratches the surface of what neural operators can do. Here are some suggested directions to continue your exploration:

-

+

Train on more complex PDEs: Extend beyond the advection equation to more challenging operators, such as diffusion or nonlinear conservation laws.

+

+Increase training scope: Experiment with larger datasets, deeper networks, and longer training schedules to unlock the full potential of neural operator learning.

+

+Generalize to the full advection operator: Train the model to learn the general operator $\mathcal{G}_t: u_0(x) \mapsto u(x,t) = u_0(x - t)$ so the network predicts solutions for arbitrary times, not just a single fixed horizon.

+

+Investigate architectural variations: Compare different operator learning architectures (e.g., Fourier Neural Operators, Physics-Informed DeepONets) to see how they perform on similar problems.

+

+...and much more!: From adding noise robustness to testing on real scientific datasets, the space of possibilities is wide open.

+

+

For more resources and tutorials, check out the PINA Documentation.

+ -#

-#  -#

-#